This is probably the most pretentious thing I’ve ever said, but I have a real weakness for Tudor houses. Therefore, Benthall Hall was probably always going to be my favourite property of the day, but not only is it a beautiful building, it has some cracking stories steeped in its walls as well.

The ancestors of the Benthall family have lived on the estate since around 1068 (hear that? It’s the sound of American brains exploding) and it was the site of a medieval manor.

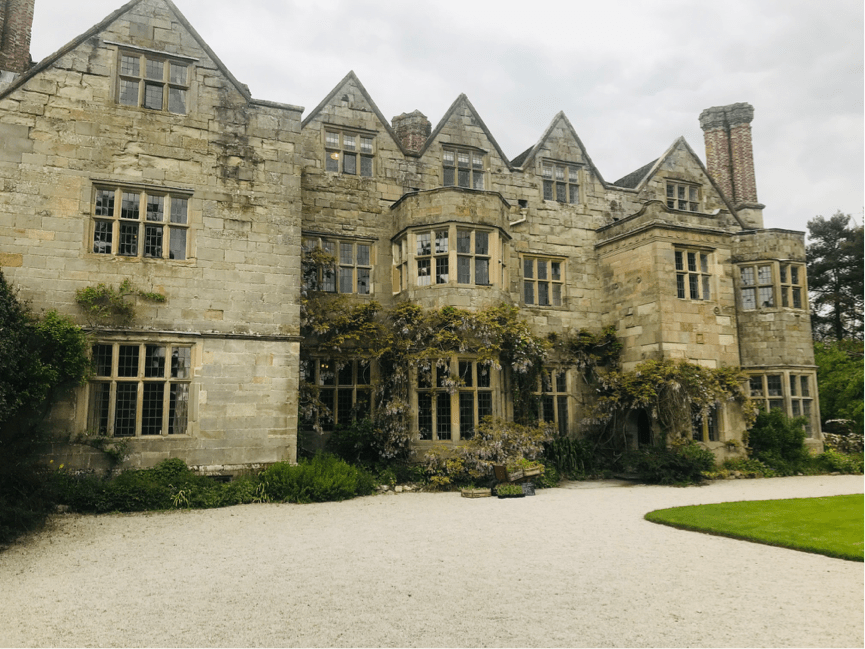

Construction of Benthall Hall (so good they named it twice) began in 1535. Just to put this into context, Henry VIII was on the thrown, he was only on wife number two (which meant Anne Boleyn still had her head attached), and the first dictionary (in Latin, obviously) hadn’t been written yet. Plus the Bible was still in Latin. So the house is old.

While the outside of the house is impressive, with iconic bay windows and trailing wisteria in full bloom across the stonework, the inside is everything you would hope it to be – with enormous fireplaces, dark panelled rooms and even a polished suit of armour standing guard.

The final room of the house to be built is believed to be the dining room, which was completed in 1610 – at which point Henry VIII and the rest of the Tudours were long gone and England was in to the Jacobian era.

And it’s in this room that Benthall Hall’s stories began for me – most of which highlight crimes against preservation of the hall’s history. Better yet, it’s another strong independent woman who we have to thank for rescuing the house from ruin. Must be something in the water in Shropshire.

The manor had been sold by the Benthall family in 1884 to a Lord Forester of Willey, who was after the acres of land that came with it and didn’t care about the house itself. Therefore, he let it out to a number of interesting tenants who made some devastating alterations to the property – more on that in a minute.

In 1934, Mary Clementina Benthall, who was living in Devon, heard the house was on the market again, so she sold everything she had and told her husband they were moving to Shropshire.

As they had no money to spend on the renovation of the house, Mary decided she would do much of it herself. Evidence of this is in the dining room, where she used a chisel to chip the white paint from the wooden panelling, leaving deep scores in the woodwork. Whoops.

The next DIY SOS disaster is in the sitting room – none of the wooden panelling fits properly. In fact in one of the corners it doesn’t meet at all. Even Nick Knowles couldn’t fix this one.

The reason behind this, believe it or not, is a cannonball. The room was badly damaged during the Civil War in 1645 when the house was being used by the Royalist troops as a garrison. Ironically, it was the Royalists who did all the damage, trying to win the house back from the Parliamentarians who had seized it.

After the war, timber was scarce, and the wood the family could get hold of to replace the damaged panelling didn’t match at all. So in typical DIY fashion, they painted it all white so no-one would notice.

The final (and most expensive) redecorating atrocity was committed exactly 100 years ago – in 1918.

As I mentioned earlier, tenants were allowed to do what they wanted to the house, so George and Arthur Maw tiled the entrance hall and another reception room with ornate Victorian tiles from their business.

Next tenant Reverend Charles Benthall took offence to these tiled floors, partly because they were too cold on his feet, and partly because they didn’t fit with the tudor style of the house. So he had the floor covered with an oak floor.

Unfortunately, in doing so, he damaged every single one of the tiles. Worse still, the tiles are so rare they would cost £2,500 per tile to have them replaced. Big whoops.

The house was left to the National Trust by Mary Clementina, with the agreement that the family could still have tenancy there, and so the Benthall family still stays at the hall for around three months a year.

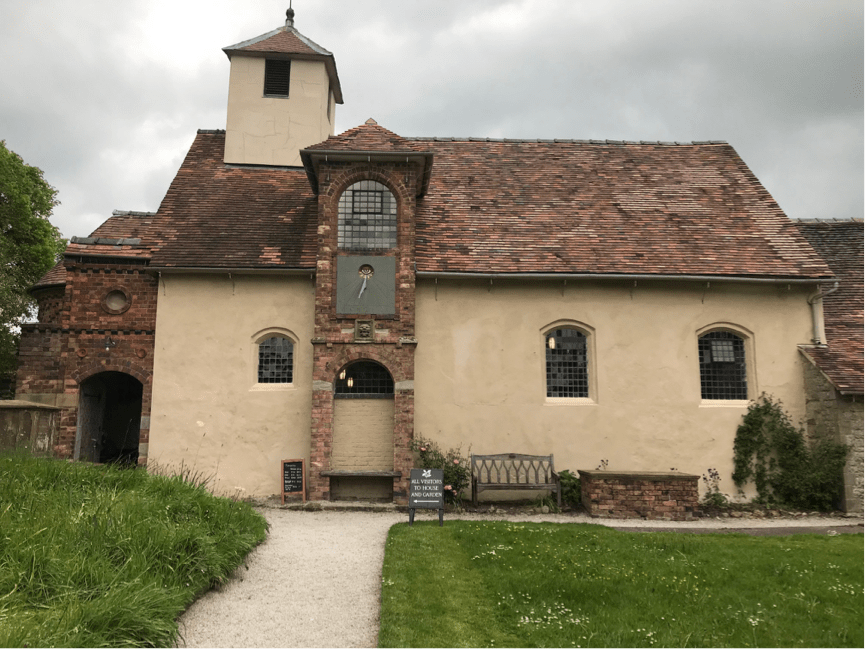

It is also worth noting that next to Benthall Hall is St Bartholomew’s Church, which was acquired by the National Trust just four years ago. The 1667 church is tiny and quaint, and wasn’t actually owned by the Benthalls, nor was it part of the estate, but instead was the local village church.

Verdict: Gorgeous Tudor house with excellent, cringeworthy stories.